East Village, Lower East Side, Loisaida, Alphabet City

... whatever you choose to call it, the neighborhood between Houston and 14th Street, and 3rd Avenue and the East River, has a fascinating history that is simultaneously unique and reflective of important national developments.

From the German cigar makers of the nineteenth century, to the Puerto Rican migrants of the 1950s and the punk squatters of the 1980s, residents of this neighborhood have created movements, defied authority, and made pathbreaking art. In more recent years, the East Village has been a focal point of gentrification as it transforms once again.

As a teacher at a school on 12th Street between Avenues B and C, I have been delving into the history of our neighborhood with the goal of connecting my students more deeply to their home, and helping them find ways to improve its future. There are so many areas in which we can make a difference, whether by defending the remaining community gardens, addressing the crisis of unaffordable housing and homelessness, or making public art to uplift the community. To truly make this happen, my students must understand the people and movements who have already made such a valuable impact on the East Village.

Community Gardens

The community gardens of the East Village are a distinctive and beautiful feature of the neighborhood. Starting in the 1970s with the Liz Christy Garden at the corner of Houston and Bowery, neighborhood residents have taken rubble-strewn vacant lots abandoned by their owners and turned them into oases of green. Anyone can stop by when the gardens are open, not just members. Organizations like Green Thumb (part of the New York City Parks Department) and the Trust for Public Land have been vital supports, but the gardens themselves came from the hard work of people who were and are determined to create space in the city for plants and humans to thrive. In the East Village and Lower East Side, Puerto Rican neighbors have been especially active in creating and maintaining community gardens.

Because land is in such short supply in the city, the continued existence of community gardens has sometimes been threatened. During the 1990s under the Giuliani administration, there was a city effort to destroy many of the gardens and open those spaces for development. Gardeners and their allies mobilized to protect the gardens, arguing that they are crucial to quality of life in dense neighborhoods with little green space. The activists succeeded in saving many of the gardens, though some sites were still auctioned off.

Community gardens have become integral to the landscape of the East Village over the past fifty years. Neighborhood residents count on them as places to enjoy calm and natural beauty.

1st st btwn 1 + 2 ave

2nd btwn B + C

6th + B

6th + B

6th + B

6th + B

6BC Botanical Garden

6BC Botanical Garden

6BC Botanical Garden

Brant Foundation Garden

Creative Little Garden

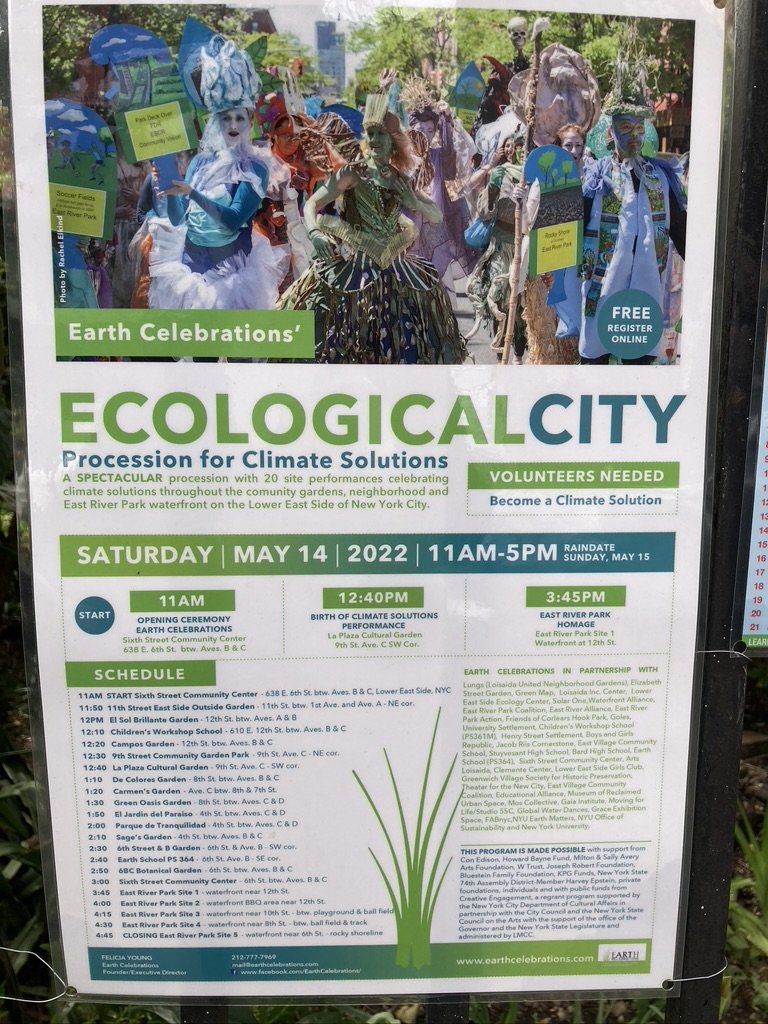

Ecological City poster

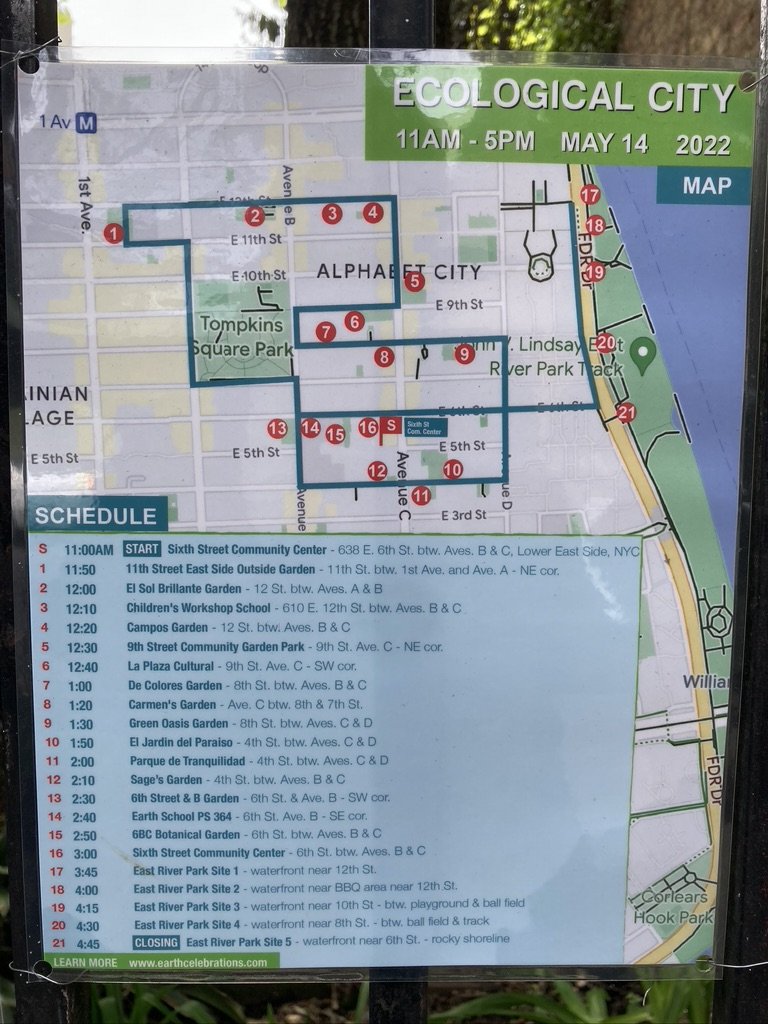

Ecological City tour map

Kenkeleba House Garden

La Plaza Cultural

La Plaza Cultural

La Plaza Cultural

La Plaza Cultural

La Plaza Cultural

La Plaza Cultural

Le Petit Versailles Garden

Le Petit Versailles Garden

LES Ecology Center

Liz Christy Garden

Liz Christy Garden

Liz Christy Garden

Lungs Community Garden Map

Peach Tree Garden

Sam & Sadie Koenig Garden

Tompkins Square Park

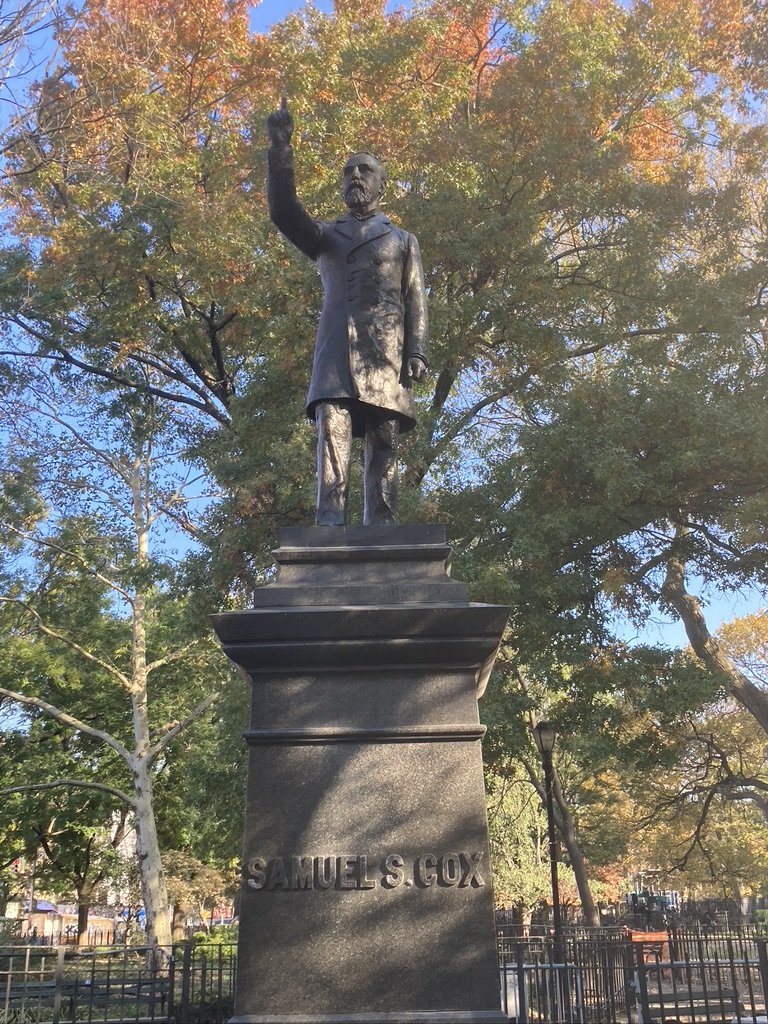

Tompkins Square Park is one of the oldest parks in New York City, dating to the 1830s. It has a celebrated and storied history—often as the site of protests, demonstrations, and even police riots. The park is on ten acres between Avenues A and B, and 7th and 10th Streets, and currently includes (among many other features) playgrounds, a mini-pool, dog runs, and a statue of U.S. Representative Samuel Sullivan Cox, sponsored by the workers of the U.S. Postal Service. At the park, one can see everyone from people struggling with homelessness, to affluent young remote workers taking phone calls, to children climbing jungle gyms.

In its earlier years, Tompkins Square Park was a gathering place for the people of Kleindeutschland (Little Germany) who lived all around it. After the Civil War, it became a parade ground with mostly open space—not much of a respite for people seeking relief from tenements. Later in the 19th century, thanks to the demands of residents, the city turned it into a park. In 1874, a huge labor demonstration was met with brutal police force. This was not the first demonstration in the park by any means, but it was certainly the most dramatic until that point.

In the 150 years since, Tompkins Square Park has been the site of countless political demonstrations, concerts, homeless encampments, Hare Krishna get-togethers, and much more. A 1988 demonstration against a park curfew led to another intense and indiscriminate police crackdown, much like the one in 1874. Nowadays, there continues to be tension among people setting up tents in the southern part of the park or along 7th Street, the police, and neighborhood residents whose views of the situation run the gamut. Alongside these areas of strain, the park is a green home to large old elm trees, red-tailed hawks, and New Yorkers seeking to relax and enjoy the outdoors.

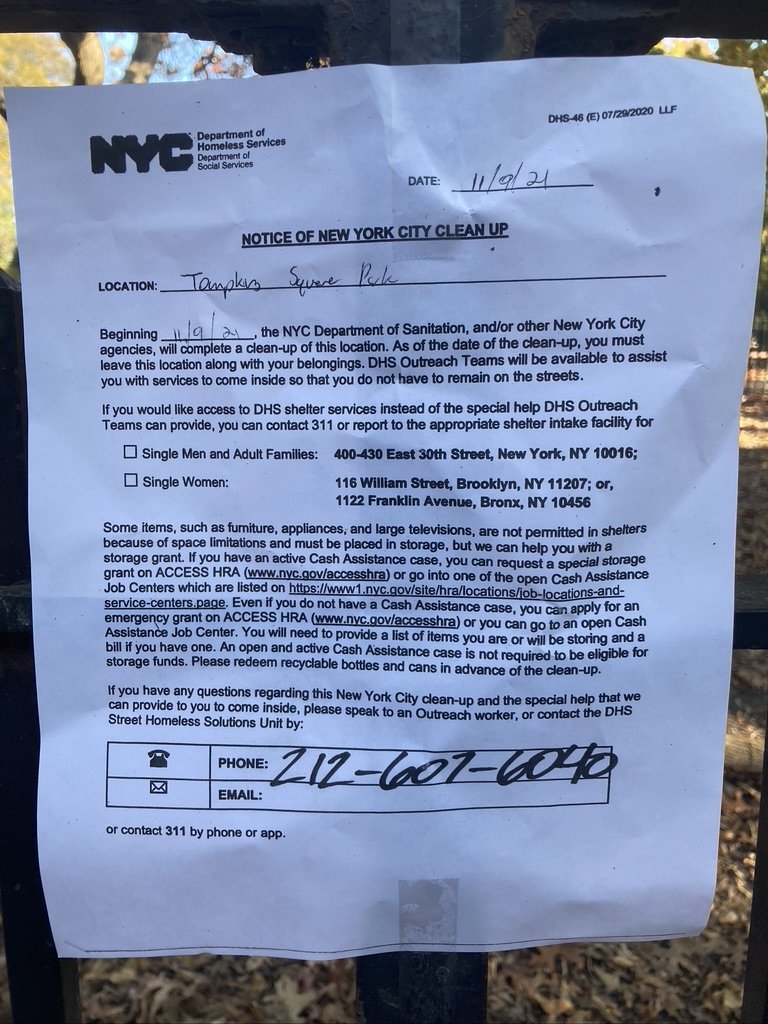

Encampment cleanup notice

Homeless belongings along 7th street

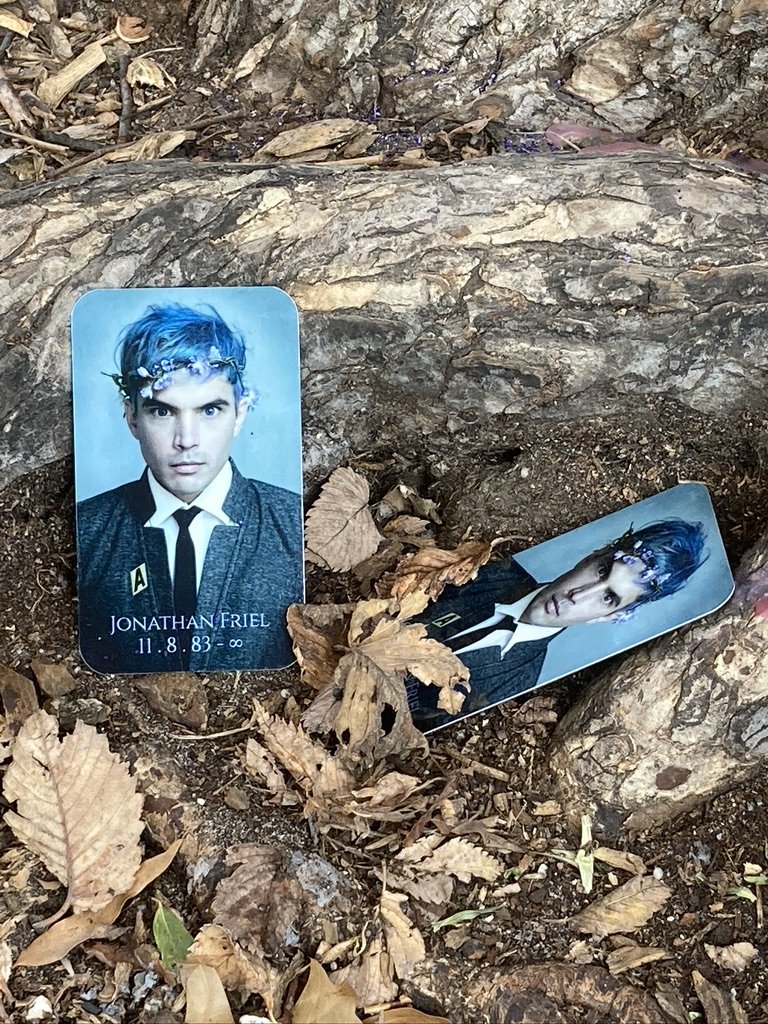

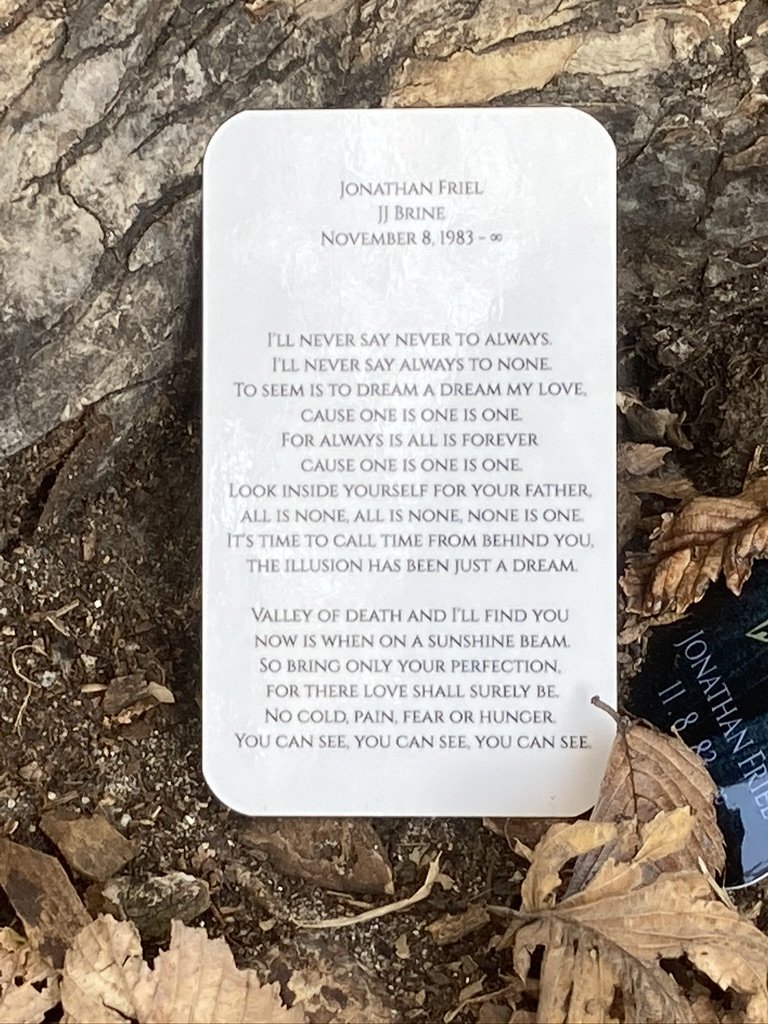

Memorial at a tree

Memorial at a tree

Memorial at a tree

Memorial at a tree

Memorial at a tree

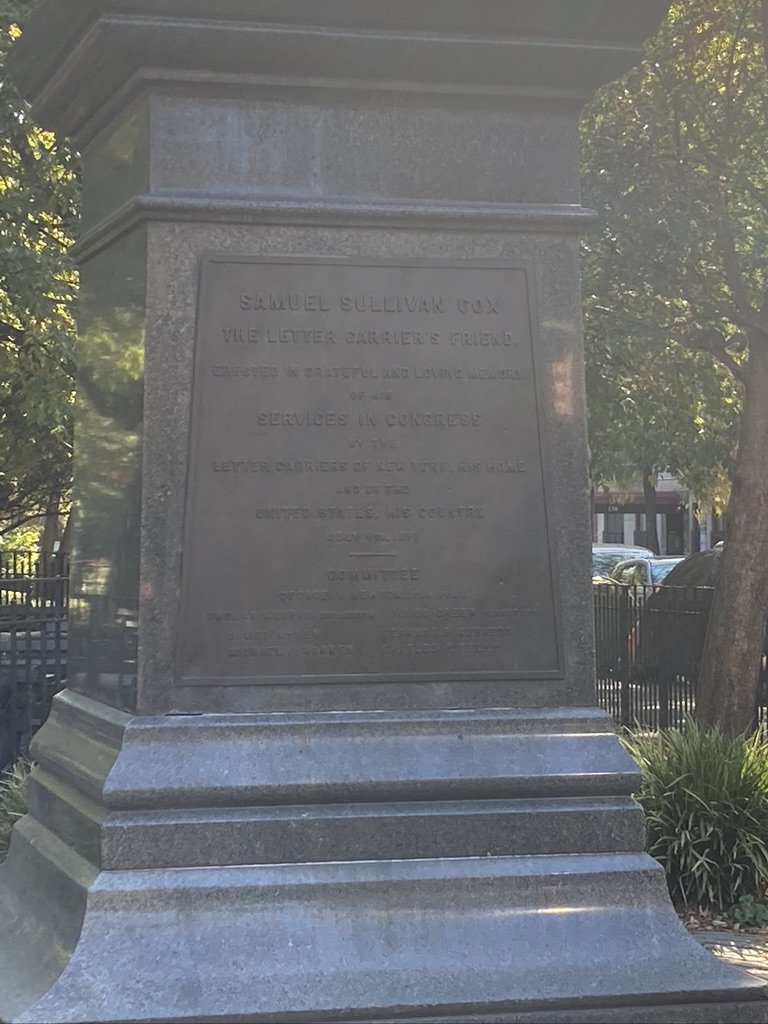

Samuel Cox statue information

Samuel Cox Statue

Sandra Turner Garden

Slocum Memorial Fountain

Slocum Memorial Fountain

Temperance Fountain - Charity

Temperance Fountain - Faith

Temperance Fountain - Hope

Temperance Fountain - Temperance

Trees

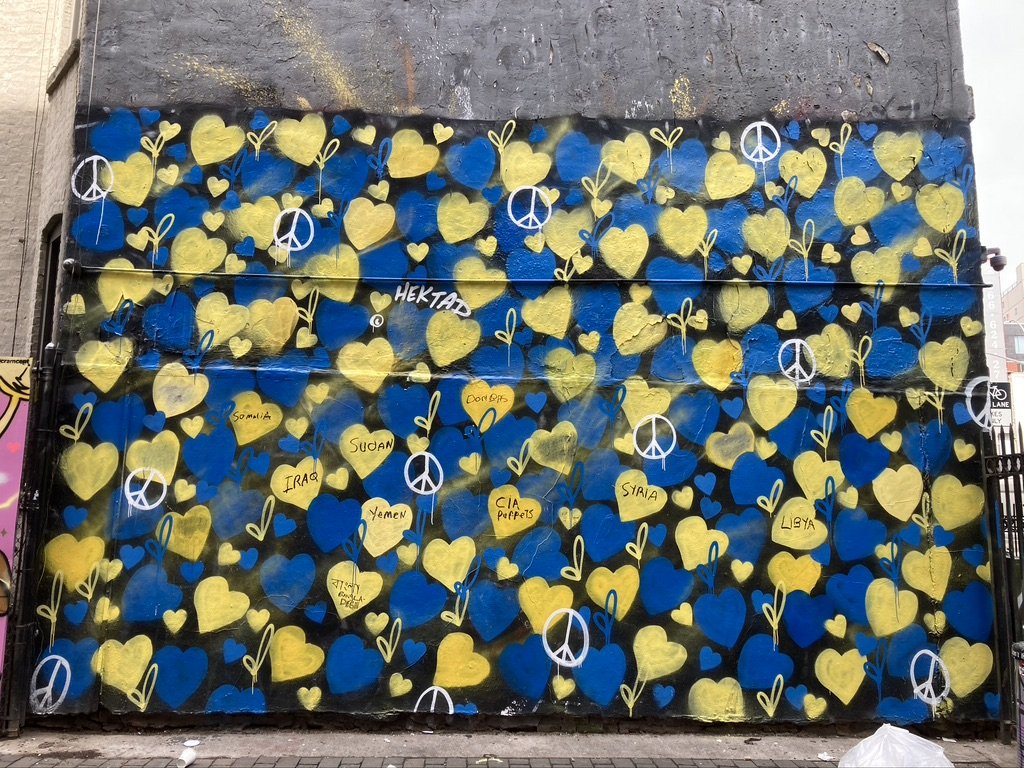

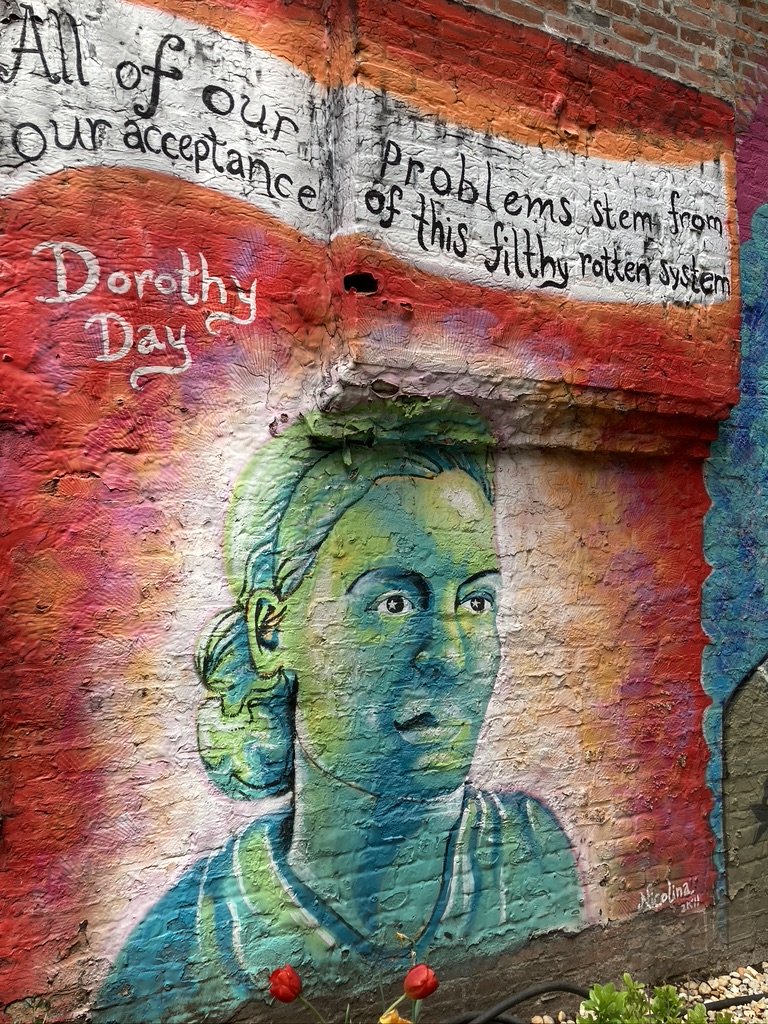

Murals + Graffiti

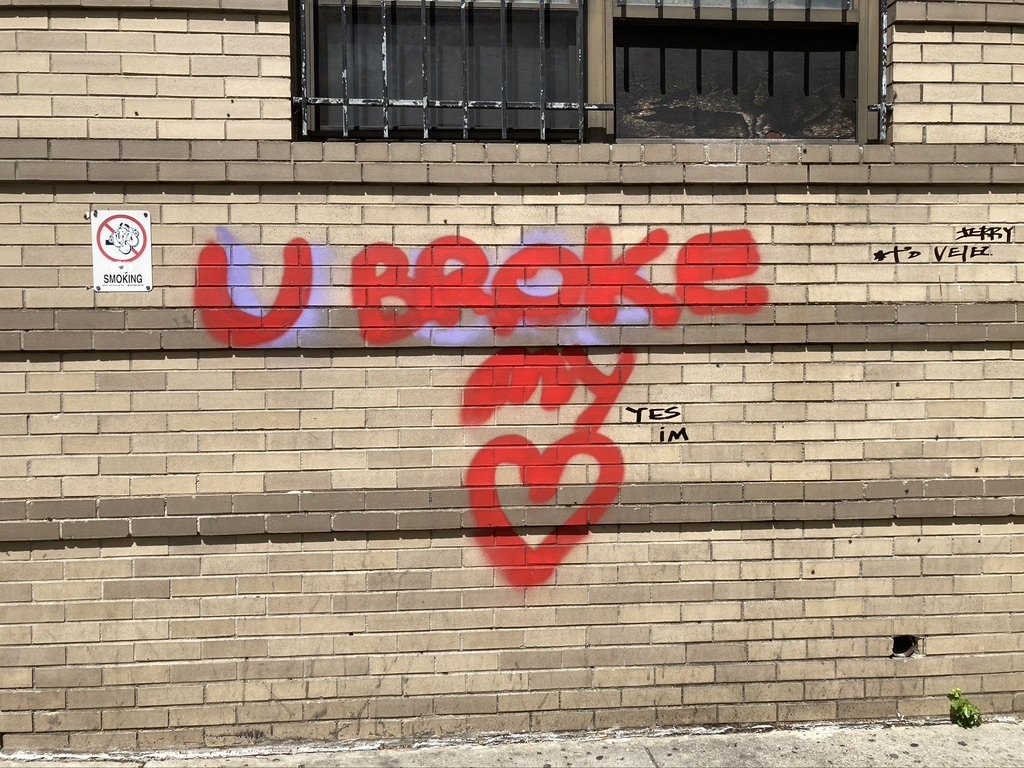

Look at almost any wall in the East Village, and you will see a mural or graffiti (and sometimes it is difficult to tell the difference). Even structures like mailboxes are often covered with tags. Murals painted by community members became common starting in the 1970s. One early site of community murals is the community garden La Plaza Cultural at 9th Street and Avenue C. One can still see remnants of the mural “La Lucha Continua” (“The Struggle Continues”), painted in 1985, a sort of second-generation mural after 1970s-era murals had vanished. Some murals, like La Lucha, are political in nature; others are more decorative; and some murals commemorate the passing of an important community member or beloved celebrity. Some of the most productive muralists include Cityarts Workshop (now CITYarts) and Chico (Antonio Garcia).

In addition to permitted murals, there are countless pieces of graffiti in the East Village. Graffiti is, of course, more controversial. Some people consider all or most of it to be an eyesore, lowering property values and contributing to a lawless atmosphere. Other people see it is a representation of free expression and neighborhood vitality. Many of us might see it as both, depending on context. Over my many years of walking from the Union Square subway station to my school on 12th Street between Avenues B and C, I have seen the long, windowless 13th Street side of the Verizon building on 2nd Avenue repeatedly tagged with the artist’s signature and then painted over, in a never-ending cycle. (I often wonder why Verizon does not invite muralists to paint on this featureless wall.)

Whatever one’s opinion of graffiti, there is no doubt that along with murals, these images invite many questions and thoughts about the meaning of community and public space. Who “owns” the visible spaces of a neighborhood? What is art and what is defacement? What are the meanings of indecipherable scrawls, to the writer and to the viewer? Why do so many people feel moved to make their mark in a public space?

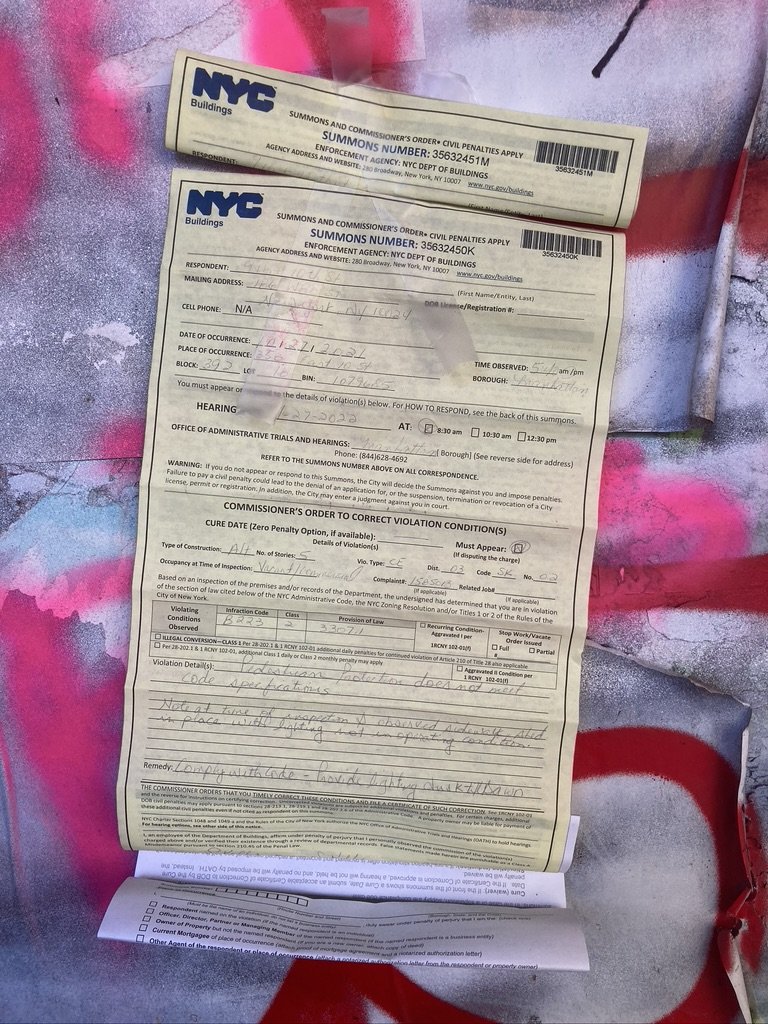

Old P.S. 64

Between 9th and 10th Streets, and Avenues B and C, on otherwise residential blocks, stands an imposing but deteriorating brick building surrounded by scaffolding. Believe it or not, this huge space has been empty since 2001.

P.S. 64 (not to be confused with the current P.S. 64, on Avenue B at 6th Street) was built in 1906 as a state-of-the-art elementary school. It was designed, along with hundreds of other early 20th-century city schools, by C.B.J. Snyder. The “H” shape of the school allows for two courtyards, one each on 9th and 10th Street. The school was open for over 70 years (and coincidentally enough, for some time in its early years, my great-grandfather, Louis Marks, was the principal!).

As the neighborhood’s population fell, P.S. 64 was closed in 1977. Soon after, the community group CHARAS moved in, designating this site “El Bohio” (the hut). CHARAS engaged in many different community projects, from the University of the Streets to building geodesic domes, as an experiment in cheap housing, under the guidance of noted architect and designer Buckminster Fuller. CHARAS rented the space from the city at a nominal rate, until the city sold the building in 2001 to a developer, who decided to evict the group.

Community support for CHARAS and protests in its defense were unsuccessful. The building was landmarked in 2006. The developer never came up with an acceptable, feasible plan for the building, and as a result it has continued to sit empty. Now, in 2022, the developer is being foreclosed on and there will be a new opportunity to use this important space, hopefully once again to serve its community.

10th street graffiti

10th street graffiti

10th street graffiti

10th street graffiti

10th street graffiti

PS 64 10th st

PS 64 call mayor bill sign

PS 64 closeup

PS 64 middle

PS 64 middle

PS 64 middle

PS 64 north middle

PS 64 SE side

PS 64 south middle

PS 64 summons

PS 64 SW next to Christodora

PS 64 SW